No matter how far you have gone down the wrong road, turn back. - Turkish proverb

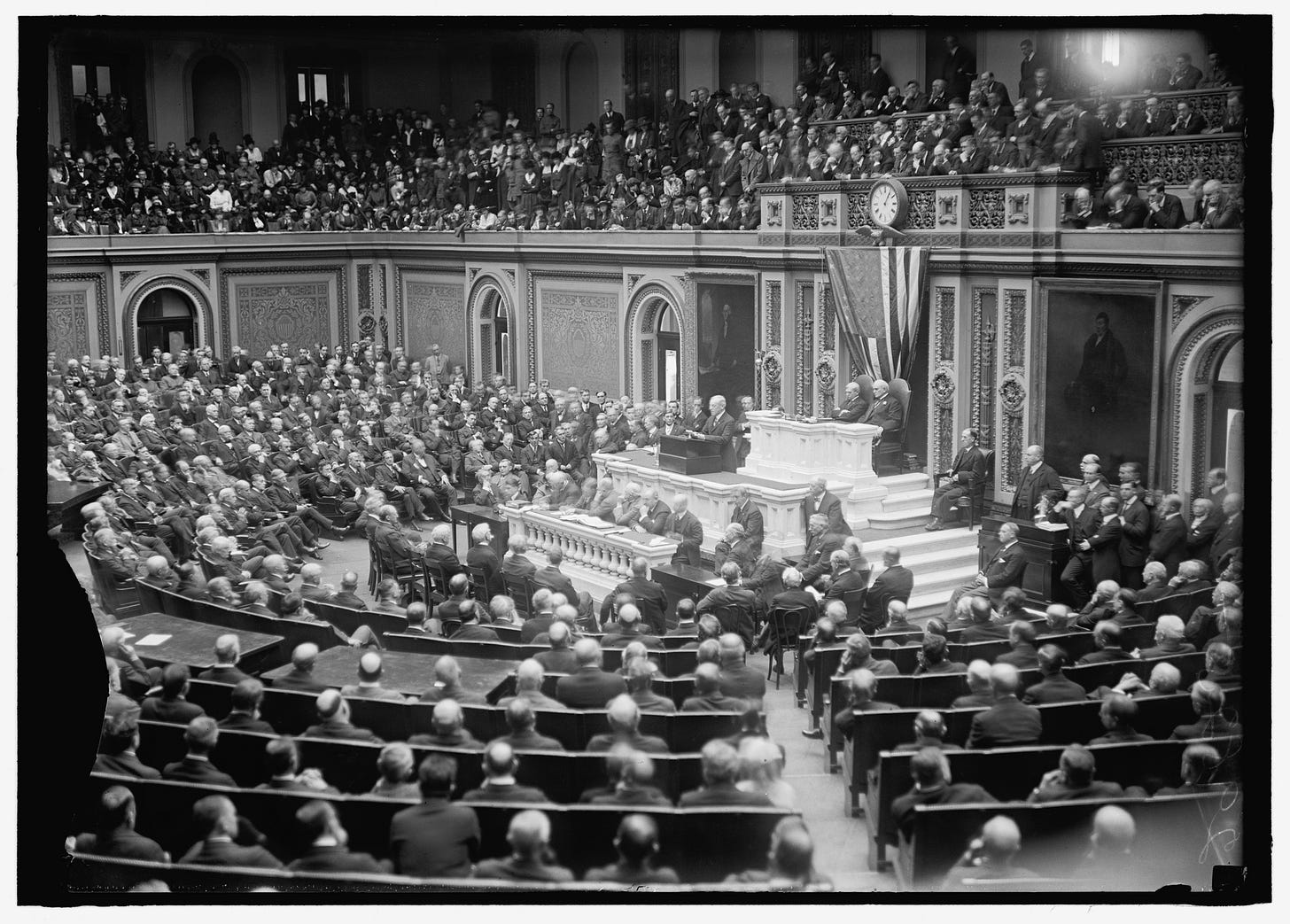

The U.S. Constitution is remarkably silent about how the House of Representatives is composed. There’s a minimum age requirement, it stipulates that representatives are allocated to the states based on population (one representative per 30,000 residents or more, not less) and that every state must have at least one Representative (no matter what its population). That’s it. The 1st United States Congress, which sat from 1789-1791, started with 59 members and ended with 65 as more states ratified the Constitution.

For the next 140 years, as the U.S. population expanded, so did the House - reaching 435 members by 1911. In 1929, with the 1930 census looming that would necessitate a further expansion of the House, the chamber passed the Reapportionment Act of 1929 which statutorily froze the size of the House at 435.

It’s been that size ever since.

This seemingly innocuous - even thrifty - change resulted in unintended consequences that weren’t recognized at the time but are glaringly obvious today.

Because seats cannot be added, the number of constituents per member has ballooned. In 1930, each member of Congress represented about 283,000 people - a manageable number even in the pre-internet (and largely pre-plane) era. Today, districts have about 768,000 (give or take and not including single-member states). To put that in perspective, if Belgium (pop. 11,500,000) had the same ratio its parliament would have 15 members (it has 150). This has made modern campaigns eye-wateringly expensive and led to an explosion of corporate and PAC money in politics. Few would argue that’s a good thing.

But the most serious by-product of the Act is its impact on the Electoral College.

Because rural, sparsely-populated states must have at least one representative, the capped size of the House created a profound rural bias in the Electoral College. Big, populous states like California, Texas, Florida, and New York are “missing” dozens of legislators - and their electoral votes.

For example, a voter in Wyoming, the most “over-represented” state, has more than three times the voting power of an elector in Texas, the most “under-represented” state. Not a single state was two times over-represented in 1804 (the first presidential election after a census reapportionment). Today, six states and DC are at least two times over-represented.

Because of this, presidents now win in the Electoral College but lose the popular vote with regularity. This has happened five times in American history, and before the 21st century they were oddities: John Quincy Adams was elected by the House after no one secured a majority in a four-way race; Rutherford B. Hayes was also elected by the House after returns from three states were contested; and Benjamin Harrison lost the popular vote to Grover Cleveland by just 90,000 votes but ended up winning the Electoral College essentially by accident - Harrison won Cleveland’s home state of New York by 1% and with it the presidency, while Cleveland enormously benefitted from viciously-effective voter suppression and disenfranchisement in the South.

In the 20th century, every President who won the popular vote went on to win the presidency.

But in the 21st century, the popular vote loser winning the presidency has already happened twice (George W. Bush earned 500,000 fewer votes than Al Gore and in 2016 Donald Trump was crushed by Hillary Clinton in the popular vote). In 2020, Joe Biden beat Trump by more than 7 million votes, but only won the states he needed to win the presidency by a mere 113,000. In short, it almost happened a third time.

It’s clear that the Founders did not anticipate or intend this to happen. By not fixing the number of representatives as they did for senators, they clearly intended the House to increase in size and serve as an equalizer in the Electoral College.

Abolishing the Electoral College is impractical. But it doesn’t mean that nothing can be done. The most sensible thing would be to repeal and replace the Reapportionment Act of 1929 with a modern bill.

A voter in Wyoming, the most “over-represented” state, has almost four times the voting power of an elector in Texas, the most “under-represented” state.

The ideal solution would be to peg the maximum district size to the population of the smallest state (since each state must have at least one representative, this will always be an at-large district). Currently, the state with the smallest population is Wyoming (pop. 577,000). Using this formula, this would elect a House of Representatives of approximately 590 members. In this hypothetical House, California would have 69 representatives (it has 52 today), Florida would get 38 (it has 28), Texas would have 51 (it has 38), and New York would have 35 (it has 26). In theory, this would eliminate the structural over-representation of small states.

This is also not an absurdly large number. The UK House of Commons has 650 members and the French National Assembly has 577. Germany’s lower house has 736 (this number fluctuates widely due to “overhang” seats - a quirk of that country’s mixed-member proportional system), Japan’s Diet has 465, and Brazil’s Congress has 513. The great State of New Hampshire? Its House has 400 members, one for every 3,300 residents.

The Founders intended the Electoral College to be broadly representative of the electorate. After all, they were trying to create a representative republic. It’s unfair to assume they could have envisaged a future when the entire population of the original 13 states was smaller than Brooklyn’s is today. It’s equally unlikely they would have wanted, anticipated, or intended the current (and growing) rural electoral bias that is now baked in like enamel paint.

U.S. elections are free and fair, but increasingly structurally anti-democratic. Repealing and replacing a misguided 100-year-old law seems like a good place to start clawing our way back.

Editor’s note: This piece was edited after publishing to remove an extraneous word.

Really good argument! How to get it done? An alliance of big states?