On November 8, 2022, an interesting thing happened in Alaska.

At the top of the ballot, Republican Lisa Murkowski defeated fellow Republican Kelly Tshibaka after Democrat Pat Chesbro’s votes were redistributed under the state’s new Ranked Choice Voting (RCV) system.

Down ballot, Democrat Mary Peltola defeated Republican Sarah Palin by ten percentage points after Republican third-place finisher Nick Begich was eliminated and his votes were redistributed between Peltola and Palin. Begich was the more moderate Republican in the race, and a majority of his voters opted for Peltola over Palin. In defeating Palin, Peltola became the only Democrat elected statewide in Alaska.

That night was a huge win for ranked-choice voting and what it can deliver for America, namely winners whose views align with a majority of voters. By implementing a non-partisan primary (the top four vote-getters advance to the general election) and RCV in 2020, Alaska adopted a gold-standard electoral system. The 2022 election demonstrated that the system worked as advertised.

So why aren’t more states adopting RCV?

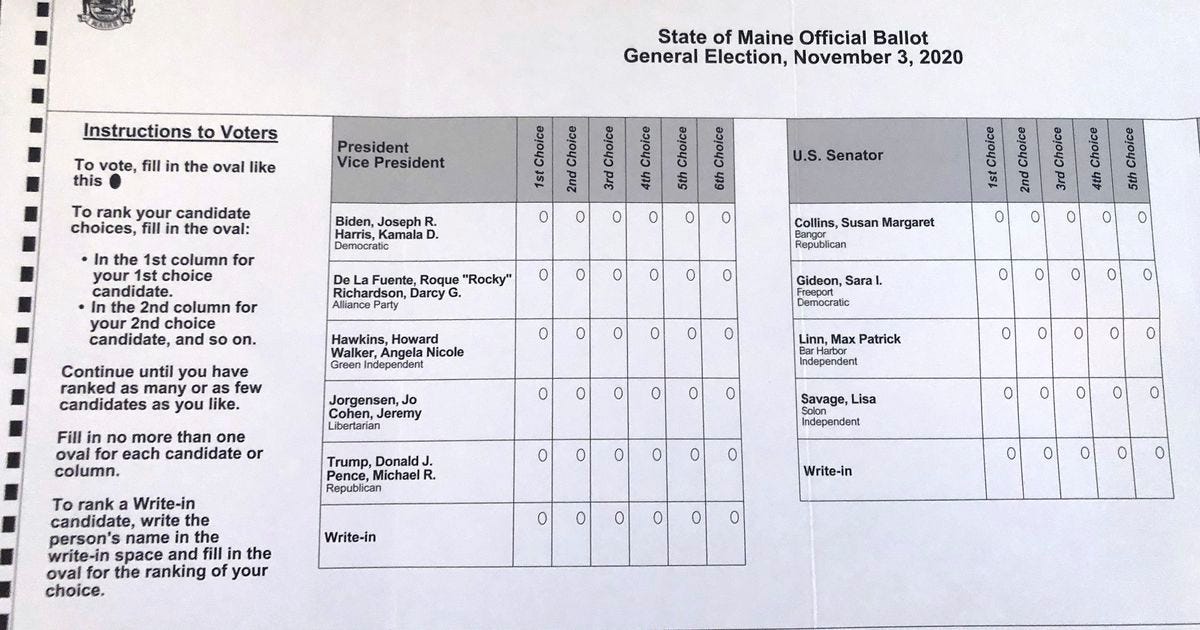

RCV is a voting system in which, rather than voting for a single candidate (often called ‘first-past-the-post’), a voter ‘ranks’ candidates in order of preference. Once the votes are tallied, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and their votes are ‘redistributed’ to the remaining candidates based on their voters’ second-choice preference. This redistribution continues until two candidates are left and one candidate obtains 50% + 1 of votes1.

If that seems simple enough, it’s because it is. In RCV, there is never a ‘lost’ voter or ‘wasted vote’. As a candidate, even if you see an opponent’s sign in a yard, you still knock on the door. Why? Because you might get the voter to give you their second preference and that vote might really matter in the end. RCV rewards appealing to the broadest swathe of the electorate and not running a base-only election to win a primary. Speaking at a Minnesota legislature hearing on RCV, Peltola testified “I would not have made it out of a primary because I’m not liberal enough.” But it turns out a majority of Alaskans like Peltola’s centrist brand of politics over Palin’s MAGA nationalism.

Opponents of RCV typically make two arguments.

The first is that it’s too confusing. Facts and more than a century of elections simply don’t support that conclusion. Australia introduced RCV in Western Australia state elections in 1907, in federal elections in 1918, and in all other states by the 1960s. So it’s been real-world tested for more than a century. The notion that voters can’t understand how to rank candidates is ludicrous; prioritization is a skill taught in primary school. And electronic tabulators make allocating preferences as easy as any other election-day workload.

Americans are also increasingly familiar with RCV. Maine and Alaska use it for all state and federal elections. Thirteen more states use it for some local elections, and three states use it for presidential primaries (which are technically party-run votes). More than 20 cities, including New York City, Cambridge, MA, Minneapolis, MN, Santa Fe, NM, and San Francisco, CA, use it for municipal races. In November 2022, Seattle, WA voted to adopt it as well.

Opponents also often claim RCV is undemocratic. They often claim that RCV defeats the will of the people since the person who gets the most (first) votes doesn’t necessarily win. In an RCV election, a second (or even a third) place finisher after the first count can sometimes go on to win. This is known as a “leapfrog”, and in the 2016 Australian federal election 11% of non-first-place winners eventually prevailed. This also happened in Maine’s first RCV election, when Democrat Jared Golden came from behind to defeat Republican Bruce Poliquan2. Shockingly, in the 2022 Alaska House special election to finish Rep. Don Young's term, who passed away, Mary Peltola finished fourth in the primary but went on to win the RCV election (and win it again that November with a big majority). But the ‘undemocratic’ argument only holds if you believe a system in which a candidate can get less than 50% of the vote and win is more democratic than one in which the winner must get 50% + 1. In other words, it doesn’t hold up to serious scrutiny.

First-past-the-post, on the other hand, can be egregiously undemocratic. In 1998, Reform Party candidate Jesse Ventura infamously won the Minnesota governorship with just 37% of the vote. And in the 2021 Canadian federal election, the Liberal Party won the most seats despite losing the popular vote by more than 200,000 votes. In two Quebec constituencies (where up to six parties contest a district), the winner won with just 29% of the vote.

On current U.S. voting patterns, RCV wouldn’t change our outcomes very much. In the 2022 U.S. House elections, there were just five races where the winner received less than 50% of the vote (above 50% of the first vote means redistributions won’t change the outcome). Two of these were the AK-AL race and ME-02, which were ranked-choice elections. In both, the incumbents prevailed. RCV in CO-08 would probably have resulted in a Republican gain after the Libertarian second preferences were allocated, and in MI-10, after the Working Class Party and Libertarian second votes were counted, the outcome would probably have been a Democratic hold instead of a Republican gain. In MT-01, redistributions wouldn’t have affected the outcome.

All in all, at least in 2022, it’s a wash.

But if Australia is a guide, our voting patterns would likely change over time.

We wouldn’t design our system today

After World War II, U.S. and Allied political scientists came together to create new, democratic systems of government for Germany and Japan. What they devised was an even more radical departure from our current system than RCV - Mixed-Member Proportional Representation (MMP). In both countries, voters cast one vote for a single-member constituency member and one vote for a party list (the two votes can go to different parties). The party vote is used to add a measure of proportionate representation to the system. New Zealand later adopted this system, and in Germany and New Zealand, coalitions are common (New Zealand has only had one majority government since MMP was introduced).

Sadly, it’s highly unlikely the U.S. will adopt MMP. But we can do the next best thing: move to non-partisan primaries, followed by an RCV election. In other words, adopt the system Alaska uses.

This would ensure that moderate, sane voices that appeal to the broadest number of people - and not just the extremist wings of each party - actually get elected to Congress. There’s no reason to delay and many reasons to move faster.

If you’re enjoying Bravely, please share it with your friends, colleagues, and family. Your support makes a big difference.

In some jurisdictions, counting stops when a candidate crosses the 50% + 1 threshold, no matter how many candidates are still left.

https://www.cogitatiopress.com/politicsandgovernance/article/viewFile/3889/3889